“In the next economic downturn there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions,” management visionary Peter Ducker predicted in 1997.

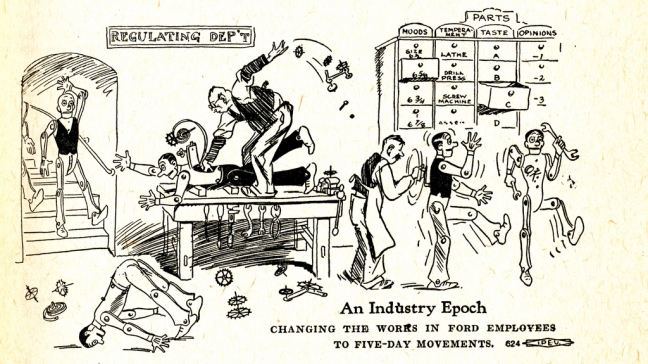

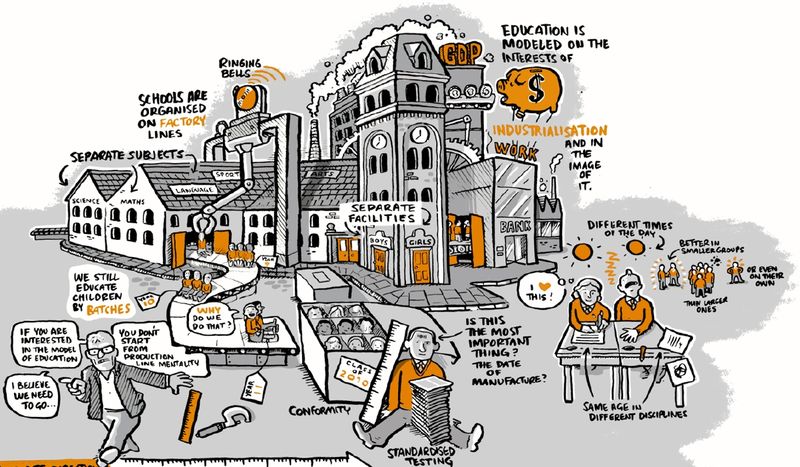

How did we arrive at the current state of the industrial economy we deal with now? Did we dehumanize the soul of craftsmanship in our efforts to dramatically improve productivity? Today’s industrial management is an enterprise that has no patience for the nuances of human craftsmanship in its urge to find ever greater manual efficiency and mass production. Most of the credit goes to Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) whose tombstone in Pennsylvania bears the inscription “The Father of Scientific Management.”

Taylor was probably the the first man in history who did not take work for granted but instead studied it. His approach to work still remains the basic foundation of the industrial economy.

In the early 1900s, the scientific method was applied to the concept of labor productivity. In The Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick Taylor described his scientific assessment of how the management of workers impacted productivity. The goal was to optimize tasks and specializations to create best practices.

Taylor observed in The Principles of Scientific Management:

Even in the case of the most elementary form of labor that is known, there is science, and that when the man best suited to this class of work has been carefully selected, when the science of doing the work has been developed, and when the carefully selected man has been trained to work in accordance with this science, the results obtained must of necessity be overwhelmingly greater than those which are otherwise possible.

Taylor conducted studies that utilized methods such as timing a worker’s sequence of motions with a stopwatch to scientifically prove the optimal way to complete a task. He determined that, for maximal productivity, the ideal weight a worker should lift in a shovel was 21 pounds. This knowledge enabled companies to then provide workers with shovels that were optimized for that 21-pound load. Formal performance measures were implemented. The result: companies saw a three-fold increase in productivity, and workers were rewarded with pay increases. It was a win-win for all involved, at least from a productivity standpoint.

The concept of productivity did not have much appeal prior to Taylor’s management methods. Skills were passed on to successive generations and learned by way of lengthy apprenticeships. Craftsmen made independent decisions about how their jobs were to be performed. Many carried out their tasks with immense passion and dedication, producing highly artistic work that was cherished for its craftsmanship. As a result, it would take a considerable amount of time to produce even articles of daily use, such as baskets, bricks, or vases.

The application of scientific methods meant that skilled crafts could be scaled down to simplified jobs performed by unskilled workers, the reason why the world may never again see the likings of another Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, or Donatello—whose works were so profound that it almost feels like they left a piece of their souls in their creations. We convinced ourselves that the compromise was worth tolerating. The goal was to mass produce products or provide services to meet certain minimum market demands.

Taylor’s methods changed the outlook of the industrial era, as well as the sentiment of these skilled craftsmen. The method took away much of the autonomy craftsmen previously enjoyed in their work. With these newly implemented best practices, though, importance was given only to efficiency and productivity.

After years of various experiments to determine optimal work methods, Taylor proposed four principles of scientific management:

- Replace rule-of-thumb work practices with a scientific method for every task.

- Scientifically select, train, and teach each worker rather than passively leaving them to train themselves as best as they can.

- Insure that all work being done is in accordance with scientifically developed methods.

- Divide work nearly equally between workers assigned to the same task, and encourage management to establish many rules, laws, and formula to replace the personal preferences and judgments of the individual worker.

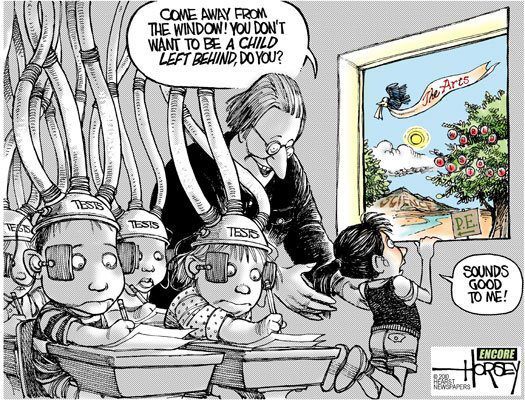

These principles were implemented in many work places, and the result was increased productivity. Henry Ford applied Taylor’s principles in his automobile factories. Even families began to perform their household tasks based on the results of these studies. The only downside was some initial resistance among workers, who complained that this method increased the monotony of their work. Ultimately, though, collective productivity took precedence over the subjective preferences of individuals. Scientific management changed the way we work, and decades later these principles were applied to hospitals and schools. Modified versions of these principles continue to be used today.

Taylor’s idea of “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work,” based on his belief that all workers were motivated by monetary reward, also took off. If a worker didn’t achieve his expected output in a given period, it was decided that he/she didn’t deserve to be paid as much as another worker who was more productive. The idea gained traction and was boldly implemented in doctors’ practices and hospitals. Since then, under industry rules, every doctor and hospital service within an individual medical facility is paid the same (more or less) amount for the same services and procedures they provide. The fees for an appendectomy, for instance, are the same whether the surgeon is fresh out of training or has 20 of experience. The more patients a doctor sees in a given day, the more productive he or she is, and thus the more lucrative his or her practice or the hospital’s bottom-line will be.

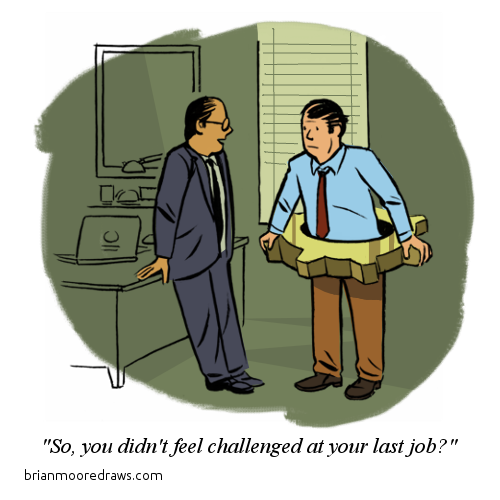

By grooming us to fit in with the rules and regulations of the industrial enterprise, we became a compliant cog in a giant machine. The idea behind this exercise was simple: people become easily replaceable if they are converted into predictable and subservient units. We can utilize person B if person A doesn’t show up to work today, for instance. This became the motto of industrial economy and has remained so ever since. Yes, all cogs contribute to the proper functioning of the society, but they are replaceable. So are you.