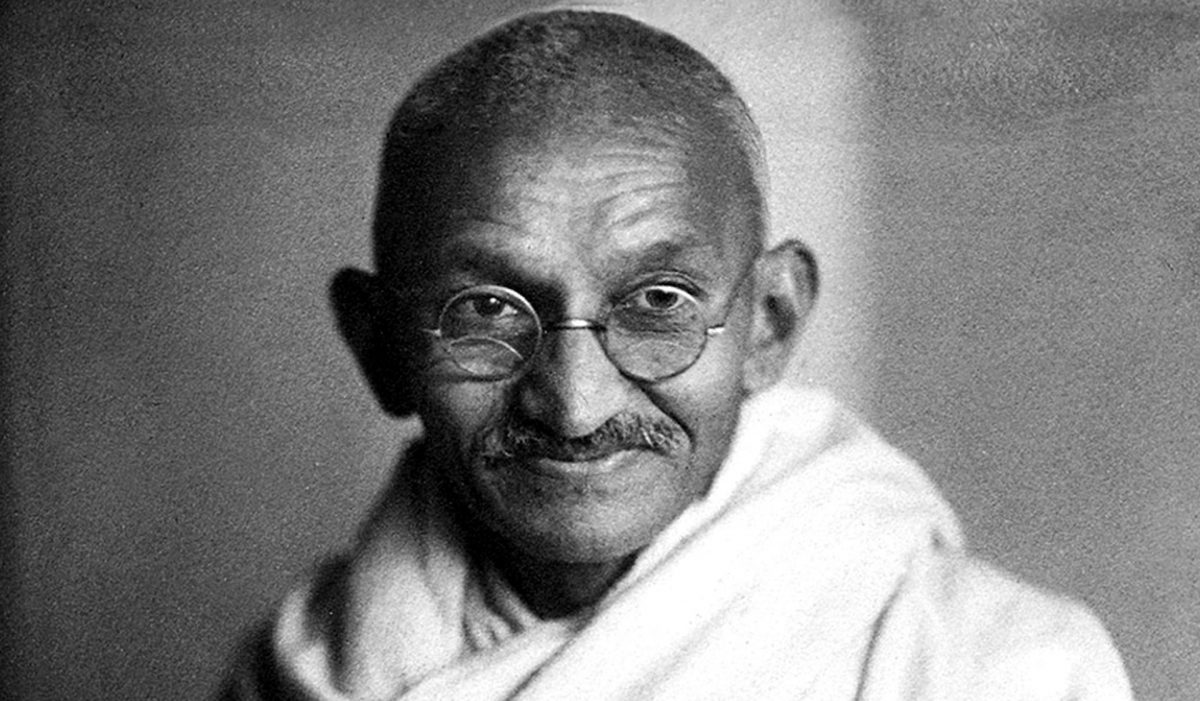

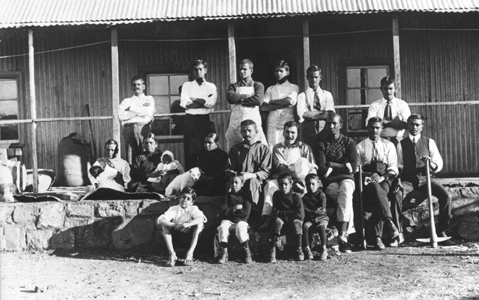

Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy exchanged a series of letters from 1909 until the death of the latter in 1910, with subjects ranging from personal beliefs to nonviolence, the struggle for freedom, and spirituality. Tolstoy’s writing greatly influenced Gandhi in his formative years, so much so that he named his second ashram in South Africa the Tolstoy Colony; there he nurtured his policy of nonviolent civil disobedience against the mighty British rule. In his autobiography, Gandhi calls Tolstoy “the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced.”

Gandhi (in the center) in “Tolstoy Farm”

Tolstoy’s writings influenced Gandhi so much that he writes:

Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You overwhelmed me. It left an abiding impression on me. Before the independent thinking, profound morality, and the truthfulness of this book, all the books given me … seemed to pale into insignificance.

Resisting the time-honored tradition of using violence to attain emancipation, Tolstoy embraced the method of nonresistance to evil. “Do not resist evil, but also do not yourselves participate in evil: in the collection of taxes, and in the violent deeds of the law courts and (what is more important) the soldiers. Then, no one in the world will enslave you,” Tolstoy writes. These particular words set a new direction for Gandhi’s future course of action.

One particular Tolstoy letter inspired Gandhi to write to him, and their communication lasted for a year.

In 1908 Tolstoy wrote “A Letter to a Hindu,” outlining his belief in nonviolence as a means for India to gain independence from the British. Tolstoy wrote the letter in response to two letters sent by anti-British Indian revolutionary and internationalist scholar Tarak Nath Das, seeking support from Tolstoy for India’s independence from British colonial rule. In 1909 a 40-year-old Gandhi read a copy of the letter when he was working as a lawyer in South Africa in his early days of becoming an activist. Gandhi wrote to Tolstoy for the first time seeking permission to reprint “A Letter to a Hindu” in Gandhi’s own South African newspaper, Indian Opinion.

In the first part of his letter to Tolstoy, Gandhi summarizes the state of affairs and the British government’s racial persecution of Asians living in Transvaal, South Africa, where he lived at the time.

October 1, 1909

I take the liberty of inviting your attention to what has been going on in the Transvaal (South Africa) for nearly three years.

There is in that Colony a British Indian population of nearly 13,000. These Indians have, for several years, labored under various legal disabilities. The prejudice against color and in some respects against Asians is intense in that Colony. It is largely due, so far as Asians are concerned, to trade jealousy. The climax was reached three years ago, with a law that many others and I considered to be degrading and calculated to unman those to whom it was applicable. I felt that submission to a law of this nature was inconsistent with the spirit of true religion. Some of my friends and I were and still are firm believers in the doctrine of nonresistance to evil. I had the privilege of studying your writings also, which left a deep impression on my mind…

[…]

But, in the course of my observation here, I have felt that if a general competition for an essay on the Ethics and Efficacy of Passive Resistance were invited, it would popularize the movement and make people think. A friend has raised the question of morality in connection with the proposed competition. He thinks that such an invitation would be inconsistent with the true spirit of passive resistance and that it would amount to buying opinion. May I ask you to favor me with your opinion on the subject of morality? And if you consider that there is nothing wrong in inviting contributions, I would ask you also to give me the names of those whom I should specially approach to write upon the subject.

In the final part of this correspondence, Gandhi touches upon a topic on which the men’s opinions grossly differed and yet maintains a spirit of genuine respect.

Gandhi writes:

There is one thing more with reference to which I would trespass upon your time. A copy of your Letter to a Hindu on the present unrest in India has been placed in my hands by a friend. On the face of it, it appears to represent your views. It is the intention of my friend, at his own expense, to have 20,000 copies printed and distributed and to also have it translated. We have, however, not been able to secure the original, and we do not feel justified in printing it unless we are sure of the accuracy of the copy and of the fact that it is your letter.

I venture to enclose herewith a copy of the copy, and should regard it as a favor if you kindly let me know whether it is your letter, whether it is an accurate copy, and whether you approve of its publication in the above manner. If you will add anything further to the letter, please do so. I would also venture to make a suggestion. In the concluding paragraph you seem to dissuade the reader from a belief in reincarnation. I do not know whether (if it is not impertinent on my part to mention this) you have specially studied the question. Reincarnation or transmigration is a cherished belief with millions in India, and also in China. With many, one might almost say, it is a matter of experience, and no longer a matter of academic acceptance. It explains reasonably the many mysteries of life. With some of the passive resisters who have gone through the jails of the Transvaal, it has been their solace. My object in writing this is not to convince you of the truth of the doctrine, but to ask you if you will please remove the word “reincarnation” from the other things you have dissuaded your reader from. In the letter in question, you have quoted largely from Krishna and given reference to passages. I should thank you to give me the title of the book from which the quotations have been made.

I have wearied you with this letter. I am aware that those who honor you and endeavor to follow you have no right to trespass upon your time, but it is rather their duty to refrain from giving you trouble, so far as possible. I, however, who am an utter stranger to you, have taken the liberty of addressing this communication in the interests of truth, and in order to have your advice on problems, the solution of which you have made your life’s work.

With respect, I remain, Your obedient servant,

M.K. Gandhi

October 7, 1909

Tolstoy writes a splendid reply to Gandhi’s letter, respectfully refusing to remove his opinion on the issue of rebirth. Tolstoy maintained that it is truth and love that drives mankind.

Tolstoy writes:

Mr. Gandhi:

I have just received your very interesting letter, which gave me much pleasure. May God help our dear brothers and co-workers in the Transvaal! Among us, too, this fight between gentleness and brutality, between humility and love and pride and violence, makes itself ever more strongly felt, especially in a sharp collision between religious duty and the State laws, expressed by refusals to perform military service. Such refusals occur more and more often. I wrote the Letter to a Hindu, and am very pleased to have it translated. The Moscow people will let you know the title of the book on Krishna.

As regards “re-birth,” I for my part should not omit anything, for I think that faith in a re-birth will never restrain mankind as much as faith in the immortality of the soul and in divine truth and love. But I leave it to you to omit it if you wish to. I shall be very glad to assist your edition. The translation and diffusion of my writings in Indian dialects can only be a pleasure to me. The question of monetary payment should, I think, not arise in connection with a religious undertaking. I greet you fraternally, and am glad to have come in touch with you.

Leo Tolstoy

Despite his differences with Tolstoy, Gandhi was able to accept and acknowledge the essence of the Russian mystic’s teaching.

Gandhi writes:

One need not accept all that Tolstoy says (some of his facts are not accurately stated) to realize the central truth of his indictment of the present system. The truth that is to be realized is love, which is an attribute of the soul that has an irresistible power over the body, and over the brute or body force generated by the stirring up of evil passions in us.

There is no doubt that there is nothing new in what Tolstoy preaches. But his presentation of the old truth is refreshingly forceful. His logic is unassailable. And above all he endeavors to practice what he preaches. He preaches to convince. He is sincere and in earnest. He commands attention.